I am currently drafting a chapter on the purpose of and problems with community studies. It is for a volume being put together by the anthropologists Billie Jean Isbel and Francisco Ferriera,“A Return to the Village: Community Ethnographies and the Study of Andean Culture in Retrospective.” They have asked contributors to describe how they originally came to their research community in the Andes, to explain how they developed the questions that directed their work, and to reflect on the value they now see in doing community studies.

I have including here an excerpt from my own contribution, “Recordkeeping: ethnography and the uncertainty of contemporary community studies.” Below I describe how I got into anthropology.

Undergraduate Orientations

The spare tire is on top of the shared taxi shown in the slide projected on the screen—this is what Bruce Winterhalder wanted us to notice. Having introduced our undergraduate course “Human Evolution and Adaptation” to the ecology of Andean farming communities, Winterhalder was taking time in class to share pictures and stories from his own fieldwork. He had taken that tire as a good sign. It seemed to indicate a well-prepared driver, savvy about the bad road that lay ahead. Winterhalder then laughed and said that the tire turned out to be a sign of the four bald tires on their vehicle. It was not a matter of if they would get a flat, but when.

This was my first anthropology class, taken in 1985, and I still remember such details. Taxis were not really our concern. Winterhalder was leading us through the adaptive advantages of coca chewing. Explaining to us how Peruvian officials and development agencies had condemned coca chewing, he showed that the claims farmers made about how coca had held up in a series of experiments—how coca allowed them to work longer, stay warmer, and forestall hunger. It was a simple and powerful lesson about anthropology: the claims a group made about their lives and actions needed to be respected and a sign of that respect was the care one took in observing, recording, and assessing those claims.

Snapshot from old photo album: Charles Mahaffey and members of our research group, Achoma, 1986

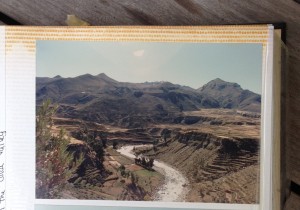

A year later, a friend and I obtained funding for summer research and, with Winterhalder’s help, we got connected to a project in the Colca valley, Peru, working for a geographer named Charles Mahaffey. When we joined up with him, Mahaffey sent us off to investigate a high, wide drainage of abandoned terraces that had been a part of the ancient agricultural landscape of the present day community of Achoma. How did the old irrigation system work? Where did the water come from? What state were the terraces and ditches in? Off we went.

For three weeks, we hiked up out of Achoma each morning, crossed over a ridge into the drainage, and got to work with our compass, altimeter, map and notebook. Eventually, we realized that the terraces across the drainage divided into two parts. There was a lower section with well-defined water channels, tightly built walls, and level surfaces for cultivating. The upper ones were rougher in every way. Perhaps they were only just coming into service when the population collapsed. Or maybe the ancestral community was cultivating something different on their highest land. We could only guess. The uncertainty did not diminish our sense of accomplishment in detecting the basic split in the agricultural landscape, a reality revealed gradually through days of scaling terrace walls and scanning among the sparse vegetation for stone-lined water courses.

Snapshot #2: Actively used terraces below Achoma, 1986

Returning for my senior year, I finished up my anthropology major. The classes began to frustrate me. Too often we seemed to finish an ethnographic case with a disclaimer that the people no longer live that way—pursuing bridewealth, worshipping cargo cults, passing through lengthy initiations, or whatever cultural issue we had just learned about. It seemed that rather than studies of cultural diversity, anthropology was becoming another kind of history. I kept wondering, “But what are they doing now?” I graduated, went to study German in Vienna, worked briefly in Europe, and then returned to Massachusetts where I worked as a salesman for a radiator factory for two years. It was not until 1990 when I enrolled at graduate school at UCLA that I worked to come up with a way to answer to that question.