Are residents of Zumbagua parish barley-eaters or potato farmers? Does it matter?

I wondered about this when I saw the difference between what men and women in Quilotoa, a community on the northern edge of the parish, said they planted compared to what they actually planted. In her wonderful book Food, Gender, and Poverty in the Ecuadorian Andes, Weismantel writes about the pressures being brought to bear on women and the future of the parish’s peasant economy in the 1980s. As she documents the labor of farming and the cuisine of the parish, she shares a quip from a man, who is curious about what it is like to fly in a plane and asked her something along the lines of, “What do us barley eaters look like from the air?” “Barley eaters” seemed an apt description for a people who took pride in the substance and strength that the crop they raised gave to the meals they prepared.

Yet, thirty years later, during a survey we did last summer, potatoes seemed to be the crop that now first came to mind.

The issue came up for me when I saw that our economic survey was not working as I had hoped it would. Our two research assistants from Quilotoa tended to push respondents to affirmative answers when they asked “Do you farm?” The follow up question, “What crops?” then became a kind of free listing exercise, an idealized statement of what a diligent household would cultivate in a normal year. It never seemed as if respondents actually thought through what they had planted in the last twelve months.

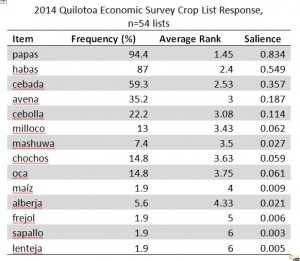

So, treating these responses as free lists, I checked to see what the most salient crops were. What seemed most central to a Quilotoan’s image of cultivated fields when asked about farming? Potatoes came out on top:

Yet, in the previous year observations pointed toward barley as being the main crop. In 2013, a part of the research team spent a week walking the dirt tracks and ridge top paths of Quilotoa recording what had actually been most recently planted in the fields.

Covering approximately 10 kilometers and recording 485 observations, they found that half the fields had been left uncultivated. Of farmed fields though, barley was planted almost twice as much as potatoes:

So, if barley still is the most frequently sown crop and if it was the symbol of identity and pride a generation ago, why is it that potatoes are the first thing to come to mind when Quilotoans are asked to about what they farm? I suspect the answer has to do with the way what people consume has eclipsed consciousness of what they produce. Quilotoa’s economy centers on tourists coming to visit the crater lake, not on farming. Certainly, people still farm, need their annual harvests, and morally value farming—hence the research assistants’ inclination to push people to affirm that they all farm. Nonetheless, most Quilotoans provision their hearths out of Zumbagua and Pujili’s markets and shops. White rice and potatoes are the core starches served in most homes.

The slipping of barley from parishioners sense of self is not that much of a surprise, but it is disheartening for anyone interested future of non-industrial farming economies. It again shows how fickle the alliance between consumption and production can be. Activists in Ecuador, the United States, and Europe who try to build sales and income for small farmers count on consumer awareness of the ills of industrial farming and the benefits of sustainably grown traditional crops to create sales. Awareness, though, is a flimsy connection from consumers back to producers. In Quilotoa, it seems to be broken even when the producer and consumer are the same person. Identity with a rich local barley faming and culinary tradition fades despite the evidence of their own fields. A far thicker swath of kitchen practice would need to be mobilized to restore barley to eminence as both an expression of identity and a product of the community.